by Edmond Lau

A great presentation consists of two important parts: well-structured content that empowers the idea that you’re trying to convey and an eloquent style of delivery that keeps your audience’s attention on your content. Both parts aim to facilitate the communication of your idea to an audience. Poor structure makes it more difficult for your audience to follow along and extract the salient points, and poor delivery detracts from the content.

An effective and general paradigm for structuring content that’s applicable to any presentation, essay, research paper, funding pitch, job application presentation, resume, or tech talk comes from what MIT Professor Patrick Winston — an AI veteran with a lecture series on How to Speak — calls VSNC. [1] Based on this structure, any compelling presentation or paper builds upon the following four cornerstones:

- a clearly defined vision statement,

- an enumeration of concrete steps toward achieving the vision,

- an articulation of salient news and results with clarifying details, and

- a summary of contributions.

Most presentations, surprisingly enough, can fit into this paradigm and become much more powerful when designed with it in mind; weak presentations usually omit one or more of these parts.

Offering a succinct and clear vision (preferably on its own slide if slides are used) early in the presentation establishes the thematic goal of the talk. It defines the boundaries of what’s relevant in the ideas presented and provides the glue that ties various points together. Succinctness and clarity in the vision ensure focus in the talk. Overly detail-focused individuals, in particular, sometimes create presentations whose themes are only implicitly defined and whose points flail around haphazardly.

Once the high-level vision is established, enumerating the concrete steps for attaining that vision gives the audience a mental path to follow and understand what’s necessary to reach the goal. The steps review progress already made and highlight what still needs to be done. Most presenters tend to get this part right since it’s a straightforward summary of completed and future work.

With the path enumerated, sharing news and details about recent accomplishments provides an excellent opportunity to enrapture the audience. Numbers, statistics, graphs, analogies, demos, and stories that showcase results often work well. Engineers tend to overvalue abstraction and to inadvertently neglect to include the details, but the details and stories are often what make the talk compelling.

Wrapping up the talk should be a summary of contributions. A common mistake is to end a well-organized presentation merely with a rehash of major points rather than crystallizing the unique contributions that the presenter or the presenter’s team actually accomplished. The contributions may be completed work that moves a field, product, or company forward or they may simply the be the refinements of ideas that offer a completely new perspective.

To make the VSNC concepts of vision, steps, news, and contributions more concrete, let’s take a look at how they apply to a real-life presentation and how they help convey ideas more clearly. Mac and technology fans look forward to Steve Jobs’s Apple keynote presentations, partly because they’re dying to know the next visionary Apple product and partly because Jobs’s presentations are extremely well-executed. His commanding stage presence definitely helps, but a decomposition of his recent March 2nd keynote [2, 3] on the iPad 2 reveals that the VSNC paradigm provides a powerful framework for understanding how his presentations are typically organized.

Jobs starts his presentation by summarizing the vision for the iPad 2 in a single, crisp slide: “Our most advanced technology in a magical and revolutionary device at an unbelievable price.”

What were the concrete steps involved in building this magical and revolutionary device? Jobs outlines the steps in these two slides, reviewing upgrades to faster dual-core processors and graphics while maintaining low power usage and the efforts to make the device even more lightweight and 33% thinner:

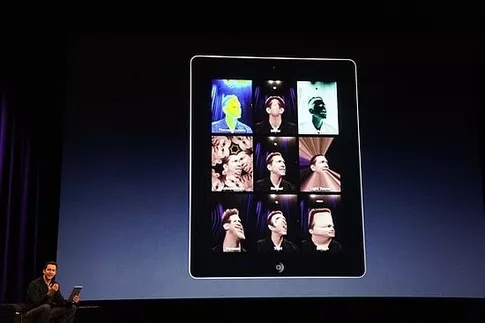

Having established the vision and the steps to getting there, Jobs pitches the new iPad 2 by going over salient news and results to get the audience excited. He chooses to do this by showcasing demos on the iPad 2 of FaceTime, PhotoBooth, iMovie, and GarageBand:

At other keynote presentations where Jobs also reviews the momentum of existing products, Jobs will often augment the news portion by sharing and marveling at numbers and details on how many iPhones or iPads were sold in the past year.

Jobs concludes with a summary of new engineering, product, and pricing contributions to convince the audience that 2011 will be the year of the iPad 2. Some of the points were previously covered in other slides; others like the statistic on 65,000 iPad apps reminds the audience that contributions made to the original iPad still apply to the iPad 2.

The application of the VSNC paradigm to Jobs’s keynotes illustrates that VSNC is a surprisingly versatile and powerful framework for both crafting and critiquing the organizational structure of presentations.

Once the content is solid, the other foundation of a great presentation is delivery and style, for which here are a few useful pointers:

- Enunciate and speak slowly. Unbridled enthusiasm for your work or your idea and nervousness to finish the presentation as fast as possible can easily lead to an overly quick delivery and slurred words. If you feel that you’re speaking at a slow and comfortable pace, slow down further to about 50% of that pace. Speaking slowly provides a variety of benefits beyond the obvious of ensuring that your audience can understand what you’re saying; it gives you more time to choose your next words, helps slow down the pace to keep you relaxed and in control, and provides more of an opportunity for you to watch the audience’s expressions and re-adjust your presentation strategy (for example, by rewording an explanation upon detection of blank faces) as necessary.

- Train yourself to avoid sprinkling your speech with “ums” and “likes,” and replace them instead with pauses. Either have a friend count your “ums” or “likes” or record your own presentation and count them yourself later. While initially uncomfortable, pauses actually sound more professional and help accentuate key points that you’re trying to communicate. Colin Firth’s Oscar-winning performance and delivery in theThe King’s Speech exemplifies how a carefully enunciated and pause-filled speech can motivate and move an audience.

- Maintain eye contact with the audience. In particular, pick a few friendly faces from the audience that appear to be reacting to your presentation. Their nods of approval and understanding give positive feedback and bolster your confidence during the presentation, and any confused expressions act as an indicator that you might need to slow down and re-explain a possibly tricky point.

- Don’t read directly from your slides. Time spent on reading slides is time not spent maintaining eye contact with the audience. Moreover, reading long sentence-like bullet points on slides conveys a lack of preparation and reduces the incentive for the audience to actually listen to you since they can just read the text faster themselves. A better approach is to list key, succinct points on the slides and to connect them together with your own words. This incentivizes you to better rehearse to have fluid transitions between points and forces the audience to pay attention in order to understand the presentation.

- Move deliberately in time with your points, so that transitions in your physical stage presence correspond to transitions in your presentation. This helps to both reduce the amount of haphazard pacing while accentuating important transitions in your presentations. If your presentation has three points, one simple way of doing this to walk in the shape of squished baseball diamond so that you walk to a new base as you transition to each point and then walk back to home plate as you conclude.

- If your presentation involves writing on a whiteboard, make sure to write with an open body that’s perpendicular to the board rather than facing the board. Facing the board while you write occludes the text or diagrams and increases the lag between when you’re writing (and likely speaking) and when the audience can actually read what you wrote.

- If there is Q&A at the end of the presentation, always repeat the question, possibly rephrasing in your own words. Repeating the question ensures both a) that the audience is able to hear the question, and b) that you’ve actually heard the question correctly and don’t waste time or look silly while answering an incorrect interpretation of the quesiton.

Skills in structuring effective presentations and delivering them clearly come with practice. Keeping vision, steps, news, and contributions in mind for any talk or presentation will make it stronger, and dissecting strong presentations and critiquing weak ones to understand how the speaker handled or mishandled each cornerstone will make your own talks better.

———-

[1] http://courses.csail.mit.

[2] http://events.apple.com.e

[3] http://www.geeksugar.com/

![ppt_slide1[1]](http://blog.pptstar.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ppt_slide111.jpg)